ANNOUNCEMENT: Introducing: The Last Autistic

This is the first article from a new Substack called The Last Autistic, written by the latest character in the Jolly Heretic universe, based autistic Asian, Lap Gong Leong! The Last Autistic is where Lap will post his speculative dispatches alongside serious articles on complex issues. Subscribe today!

Thursday March 7th, 2024

It was one in the morning in Budapest’s Jewish Quarter. I couldn’t sleep, so I decided to walk around the neighborhood. A homeless man slept peacefully outside a grocery store. Open-air tables were full of exuberant Budapesti drinking themselves silly. Two nubile blondes sang “dancing queen” inside a karaoke bar. Two sophisticated Beijingers were engrossed in conversation. Jet lagged, I finally my sojourn ended with a Filet-O-Fish meal. Wandering around at night never felt so safe.

The next morning, I joined a group tour led by a brunette matron. The bus passed through several upmarket streets including Andrassy Avenue, Budapest’s Champs-Elysée. After disembarking at a grand square, the guide started talking. “Heroes’ square, built in 1896, commemorates 1000 years of Hungarians living in the Carpathian Basin. The first Hungarians originally hailed from the Ural basin.” Her impassioned rhetoric took me by surprise. I couldn’t imagine sober Manhattanites speaking about Union Square in the same way.

The bus then took us to the castle district. Located in residential and hilly Buda, the district was the city’s premier tourist attraction. Unlike Paris’ Eiffel Tower, the district was in a class of its own. Upon arriving, I saw a bustling construction site located across the Fisherman’s bastion and Matthias Church. An ancient building was being reconstructed. “What is this place?” I asked. “It’s an old castle that was bombed out during the second world war. It is being rebuilt under the Hauszman program.” Seeing Hungary spend its newfound wealth reconstructing old buildings aroused some personal bewilderment. Yet I still felt deeply envious because the Hungarians were rejuvenating grand dames with an authentic zeal that eluded similarly successful New Yorkers. The tour guide and I started talking about Viktor Orban. She was deeply supportive of the infamous premier. “Orban cares deeply about Hungary. He’s keeping us safe from leftism and is slowly making Hungary more prosperous she said. If her words weren’t so heartfelt, I’d have thought she was speaking under duress. Her honesty made it difficult to think about anything else.

The next day, my father and I went on a day-long group tour. A heavyset woman in her mid-sixties, Katalin, led the excursion. During a pit stop in Esztergom, I asked her “Is there anything I can give my mother?”. Katalin led me to a small tent. “This is real Hungarian paprika. You can use it for soups or as seasoning. Your mother will love it”. On the river cruise back to Budapest, I sat down next to Katalin. How are you enjoying your trip?”, she asked. “I’m utterly amazed at Hungary’s strong sense of identity”. “For a long time, it was all we had. This is home”, she said. Later, I presented the bags of paprika to him, my father asked me “Why did you buy this? “I thought mom would like it.” “Why would you think that?” he said.

“Can’t we just go directly to Vienna, dad?”. It had been 4 days. Our Eastern European stopover had become exhausting. “I already told you about the plan to see Pannonhalma and Bratislava!” Dad said. While guarding his bags, an absolute giant of a man entered the lobby. “Chris? I’m Balint. I’m ready to drive you to Vienna when you’re ready”. Balint was a positively gargantuan man that looked more like a soldier than a driver. “I’m his son, Lap. Chris is finishing up his breakfast.” My father finally arrived, “Ready to go?” he said.

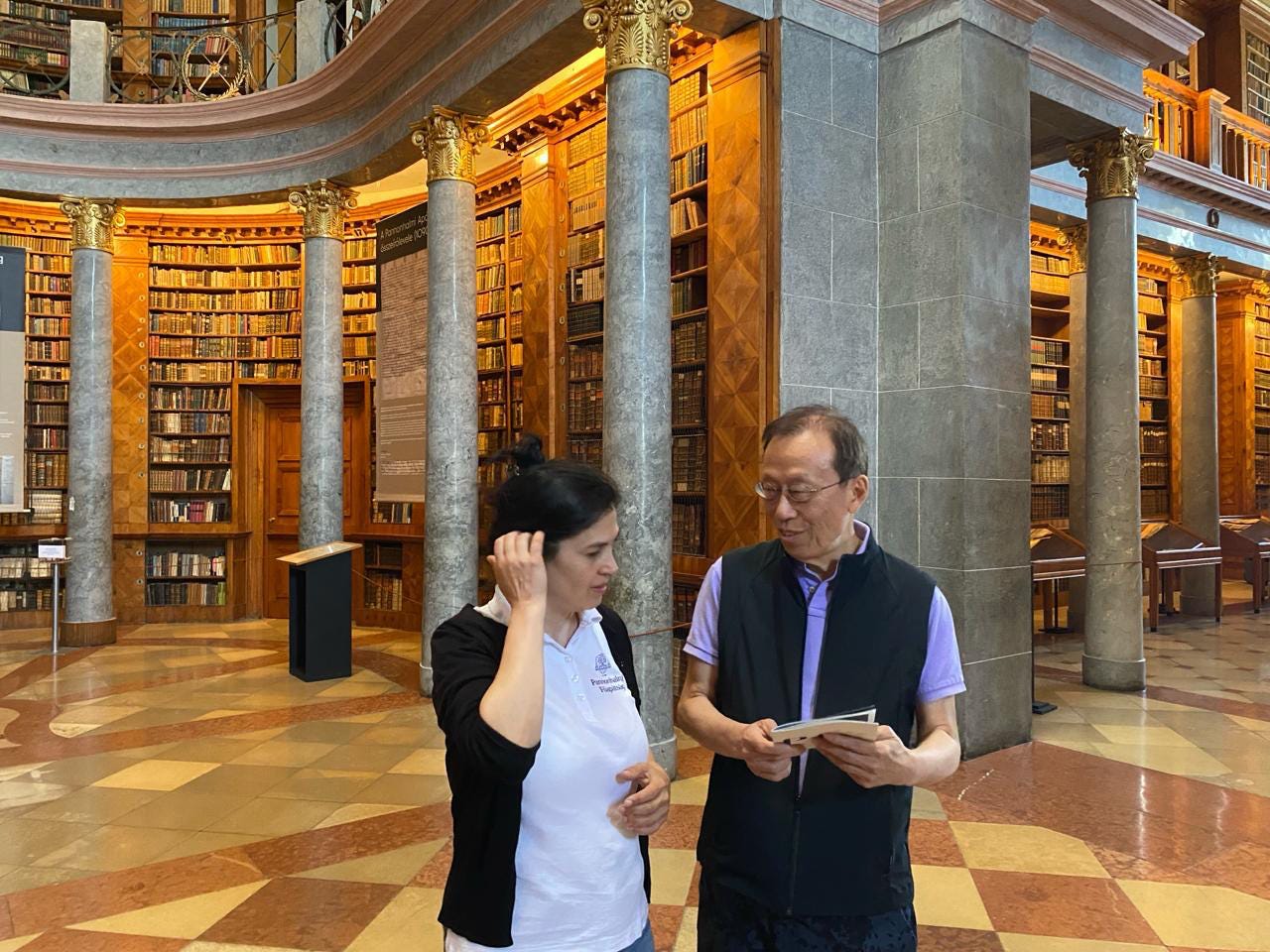

An hour later, we were on the outskirts of the Pannonhalma Archabbey. “If you need to go to the bathroom or have a snack, I suggest you do so now. There aren’t many service stations between here and Bratislava” Balint said. The Archabbey was majestic and ancient, surrounded by bucolic farms. Dad and I were both awed by her pristine state. New additions accentuated the ancient handiwork, making the palace stronger than the sum of its parts. “What’s that room over there, Dad?”. “That looks like the crypt, do you want to go in?”. “No, it looks scary.” We ventured into the cloisters and then to the library. If poorer and traditionalist Hungary maintained such splendid and awe-inspiring architecture, what did that say about her far wealthier and progressive neighbors?

Hungarians seemed to possess an idiosyncratic character that resonated with me. Even their politicians expressed personal beliefs with a frankness that most Congressman could only dream of doing. Seeing Budapest’s magnificent riverside parliament, photographing the reconstructed classical buildings, and conversing with genuine people was truly special. However, hearing potent Hungarian stories elevated a stopover into a journey.

When Hungarians told me about their country’s struggle with communism, I thought about the thousands of times Hong Kong people gathered and sang “Glory to Hong Kong”. When I looked at the derelict buildings that were slowly being restored, I thought of the derelict shophouses in Central. Katalin told me about her struggle adapting to capitalism in the 1990s. She was no longer young and needed to start over from scratch because her recently privatized employer made cutbacks. My sister-in-law struggled with underemployment after being laid off from her dream job. Balint’s lifelong struggle with ADHD, reminded me of my own unrewarding quest to overcome Autism. His comprehensive intellect and an imposing physique somehow didn’t make school easier. His teachers were dumbfounded by his erratic performance and were unable to accommodate his special needs. “School was very hard for me. I’d often have trouble paying attention in class.” Balint grew to become a talented basketball player and aced his university entrance exams. He became a self-employed entrepreneur after graduating with a degree in hotel management and Economics. He seemed to have left disability behind.

“Do you think Hungary could become a developed country”, I asked. “Yes, but the Hungarian mentality is a huge roadblock” he said. “What is the Hungarian mentality?” I asked. “The Hungarian mentality is a profound sense of pessimism. It is also a fear of losing what little you have.” “We went from being one half of a vast empire to losing two thirds of our land and much of our people. We were a prosperous kingdom that became poor and backward.

Throughout history, different invaders stayed for ages. Even with independence, deteriorating prospects always lead to someone else invading. Hungarians feel there’s no point of working hard because someone or something is going to take it away. You must understand that for most of Hungarian history, things always got worse. We spent around half of our history being colonized or co-opted by someone else.” His forthright honesty rendered me speechless. “But aren’t things better now?” I said. “Yes, things are getting better, and the economy is growing. Success will take a while longer, but you no longer need to leave Hungary to make a living anymore.”

If the Hungarian mentality was defined by enduring and powerful pessimism, then I was struggling alongside a nation.” Perhaps every Hungarian’s perpetual dread also began with overbearing teachers and underwhelming test scores in the second grade. “The teachers didn’t know how to deal with me, that lead to trouble”, Balint said. My teachers reprimanded classmates for insulting me, only to dress me down in front of them. “If you put so much effort knowing American presidents, why don’t you put in the effort to understand ratios?”. Every year, more middle-brow peers surpassed me. Why even put in any effort into anything if others were always getting ahead? Eventually, being self-indulgent was no longer an option. Even mom and dad couldn’t placate me forever. The Hungarians who sacrificed their lives to preserve their independence, knew there was no alternative to self-sufficiency. Balint believed his pessimism came from the threat of losing everything. “How did you learn how to manage for ADHD, Balint?” “I exercise every single day and meditate at night. On some days, I’ll run. On other days, I’ll swim. Sometimes, I’ll bike.” “You don’t take medication, Balint?” “No, I don’t. The exercise and mediation help me concentrate. You should try it” he said. “Nothing comes easy, it took me years to learn how to gain control of myself”. If he could conquer obesity, then why couldn’t I do the same?

By the time Balint dropped us off at St Stephen’s Square in Vienna, Dad and I knew we returned to western civilization, with all her amenities and ingrained prejudice. The city’s pristine streets and white facades upstaged even the most meticulously restored villas in Budapest’s Inner City. Her handsome cobblestone streets complimented her sophisticated residents. Her serene cafés and absolute quiet imbibed a sense of peace. Yet, this perfection felt ephemeral. Vienna’s palaces, parliament, and tramways may have outclassed everything eastward, but she didn’t seem to possess the same confidence. We may have been much richer, but were we truly better off than the Hungarians?